The Oldoini cousins couldn’t have picked a better mark than Napoleon III. A notorious womanizer, Napoleon also “suffered” from a chaste and pious wife, Empress Eugenie who had long stopped sleeping with him because she found him and his extra-marital escapades “disgusting.” Well enter: The Countess of Castiglione.

Although the still-teenaged Oldoini jumped at the chance to go to Paris and get away from her hum-drum life, there was one big wrench in her plans. Count Franceso went with her, and everybody knows that a middle-aged husband can really cramp your courtesan style.

There’s no doubt that the French court was initially obsessed with the countess, and she became the “It Girl." People called her beauty “a miracle” and named her as “la divinia contessa.” You know you’ve made it when someone compares you to a literal goddess. But for all this praise, not everyone was as enamored…

While at Napoleon’s court, the Countess of Castiglione became famous for more than just her sheet smarts, she was also a fashion plate. Courtiers were delighted with her flamboyant entrances to parties, and her costumes were always impeccable.

The countess may have had a mystical hold over men, but her allure had one major flaw. She was, in a word, extremely vain. Many times, her self-absorption got the better of her and instead of seducing her dancing partner, she only made them yawn. As one of her contemporaries put it more sharply, “After a few moments…she began to get on your nerves.”

The Countess of Castiglione had no love lost for Empress Eugenie, Napoleon’s wife. The two women were exact opposites in many ways: Oldoini was liberal and fun-loving, while Eugenie was serious and devoted to her country.

Prim, proper, and dutiful Eugenie had to suffer in contempt when she got the full view of the Countess of Castiglione’s costume, and I do mean the full view. The dress, while dotted with hearts, was almost entirely see-through, and the countess wasn’t wearing a corset. And that's the reason why it became infamous.

The countess’s meaning wasn’t lost on Empress Eugenie, and the straight-laced woman ended up getting in a savage comeback. Eugenie reportedly found a way to waltz over to the barely-dressed countess. Once there, she looked the courtesan up and down before sniffing, “The heart is a little low, madam.” Translation: Your cleavage is showing!

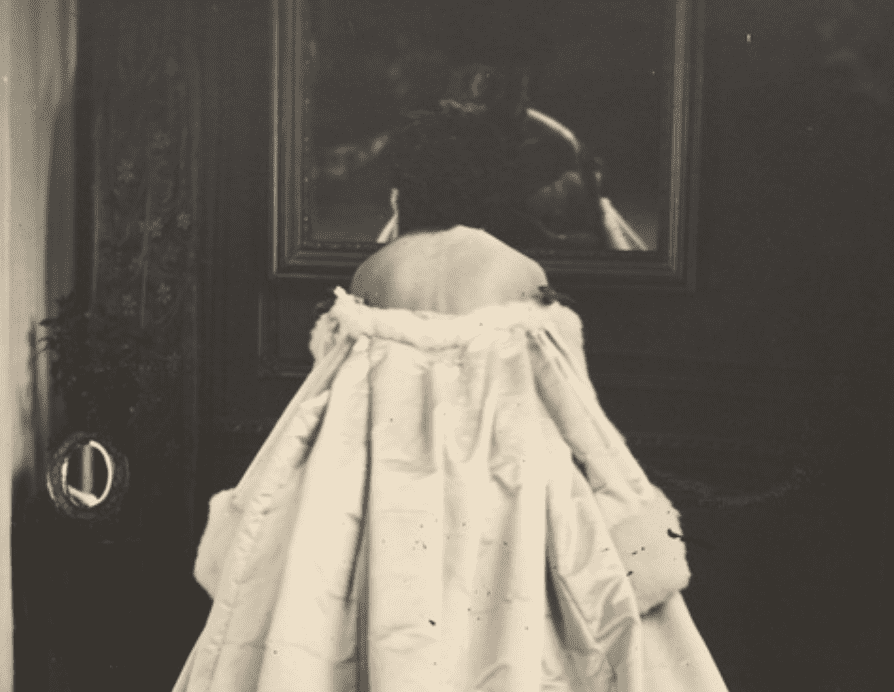

Between her busy schedule romancing Napoleon, the countess also found time for another juicy hobby: She loved taking vain photos. Oldoini turned self-obsession into a cottage industry—in fact, it’s what she’s famous for today. After teaming up with photographer Pierre-Louis Pierson, Oldoini amassed over 700 19th-century “selfies.”

In hindsight, it’s not a very good idea to send a teenager into enemy territory with instructions to sleep her way to the top. Soon enough it all came crashing down. Turns out that while Napoleon and the countess were very pleased with themselves, Francesco wasn’t so ecstatic.

In the end, Oldoini’s illicit dalliance with Napoleon III was as short-lived as it was tragic. By 1860, their affair had soured, and the countess had completely lost favor at court. The reasons for her sudden fall from grace remain a private mystery.

Oldoini never did reconcile with her husband—and though this would get her into trouble later, she didn’t much mind for the time being. She returned to Italy only briefly after her royal affair fell apart, but she just couldn’t stay away from her beloved France. She went back in 1861 and stayed for good…getting into a lot more trouble in the meantime.

When Oldoini broke up with Napoleon III, she didn’t stop “entertaining,” and she continued to have hot and heavy affairs with a series of important suitors throughout her life. She wasn’t cheap, either. Reportedly, the Marquess Richard Seymour Conway once offered her 1 million francs for just 12 hours of her “company.”

The Countess’ early photographs drew on characters from mythology, Biblical symbolism, literature. She is Queen Anne Boleyn, Queen Eritrea, a corpse, a nun. Her favorite prop is a mirror.

Oldoini showed an odd attachment to her only son Giorgio, but it didn’t stop at doting. She also insisted on photographing him constantly, pulling him into many of her projects and often making him serve as her stand-in when she set up shots. As a result, he became the most photographed child of the 19th century.

In 1871, things weren’t looking good for the Countess of Castiglione. Prussia had just absolutely destroyed France in the Franco-Prussian war, and German forces were considering occupying Paris and threatening the countess’s luxurious way of life. But it turns out that Oldoini really shone when her back was up against the wall….

It wasn’t all disreputable behavior in the court of Napoleon III, and the countess’s proximity to the emperor threw her into the paths of some of the most important figures in Europe at the time, including legendary German statesman Otto von Bismarck, who was like Angela Merkel.

Even after her tenure as a royal mistress, the countess played an important role in European politics. While Germany was considering occupying France, Oldoini’s old friend Otto von Bismarck called her up personally and set up a secret meeting to ask her advice on the matter. The countess’s totally unbiased response? “Nah, you don’t wanna do that.” Guess what? He listened.

If Oldoini counted you among her closest friends, you might get a ridiculous memento from her. Throughout her life, the countess made use of her famous photography habit and would often send albums to her nearest and dearest…all filled with picture after picture of HER. In case it’s not clear yet, the Countess of Castiglione wasn’t a girl’s girl. She actively spurned the company of other women, often refusing to even talk to them while she was at balls. Instead, she preferred to stand in the middle of the room and let men fawn over her “as if she were a shrine.”

Before you go accusing Oldoini of being a good-for-nothing influencer, consider this, she was deeply involved in the production of her “selfie” photos, essentially acting as her own art director. She was notoriously obsessive about this aspect of her work, repositioning the camera with exact precision when she didn’t like what she saw.

Before you go accusing Oldoini of being a good-for-nothing influencer, consider this, she was deeply involved in the production of her “selfie” photos, essentially acting as her own art director. She was notoriously obsessive about this aspect of her work, repositioning the camera with exact precision when she didn’t like what she saw.The countess was one of the first airbrushers. Hand-painted photographs were a luxurious novelty at the time, so naturally Oldoini made the best use of them she could. Whenever she wasn’t perfectly satisfied with a photograph, she’d use hand-painting to soften her unflattering angles and put herself in the best light.

Some scholars argue that the Countess of Castiglione wasn’t just the first model of our time—she was also the first supermodel too. Her photographs weren’t just about the clothes she was wearing but also about who was wearing them.

Despite her prickly nature, the Countess had rabid fans long after she passed. The poet and dandy Robert de Montesquiou was obsessed with her even when she was alive, and his ardor only grew. He eventually collected over 400 photos in her massive collection, which are now housed in the Metropolitan Museum of Art.

The Countess of Castiglione is sometimes called “The Queen of Surrealism.” Her playful photoshoots anticipated the Surrealist aesthetic that would dominate the art scene after she passed In one meta photo, she peers at the viewer through a camera—drawing attention to the ways she’s both looking at you while you’re looking at her.

Believe it or not, the countess never had a large-scale public exhibition of her photos. This was all supposed to change at the turn of the century, when the aging model finally had big plans to display her collection of over 700 photos at the Exposition Universelle in Paris. Most tragically, this was not to be…

Sometime during her separation proceedings, the Countess of Castiglione’s estranged husband decided to ramp up the bitterness and do something truly horrific. He tried to claim custody of their only son Giorgio, using his wife’s lavish lifestyle as proof of her bad mothering. The countess’s response was swift and brutal. When Francesco tried to claim custody of her only beloved son Giorgio, the Countess of Castiglione didn’t take it lying down. Instead, she sent her ex a “present” in the mail. When he opened it he was horrified. It was a seemingly innocent photograph of the beautiful countess dressed up in a luxurious gown—but when the count looked closer, his blood ran cold.

Sometime during her separation proceedings, the Countess of Castiglione’s estranged husband decided to ramp up the bitterness and do something truly horrific. He tried to claim custody of their only son Giorgio, using his wife’s lavish lifestyle as proof of her bad mothering. The countess’s response was swift and brutal. When Francesco tried to claim custody of her only beloved son Giorgio, the Countess of Castiglione didn’t take it lying down. Instead, she sent her ex a “present” in the mail. When he opened it he was horrified. It was a seemingly innocent photograph of the beautiful countess dressed up in a luxurious gown—but when the count looked closer, his blood ran cold.

In her later years, the Countess of Castiglione barely left her house, considering it the height of mortification to show her slightly wrinkled face to the masses. When she did leave, she would wear dark veils and only go out at night so she could cover all evidence of her “shameful” age. Sadly, as we’ll see, she might have had a darker reason for this behavior. Despite her self-exile later in life, the Countess of Castiglione still found time to do the occasional photoshoot.…but the results were chilling. Critics have noted how “morbid” her late period images are, with the countess doing things like placing herself inside a coffin and posing with the corpse of her late terrier pup.

The Countess of Castiglione’s self-seclusion was rooted not just in vanity but also in tragedy. In 1879, little Giorgio passed from smallpox, predeceasing his utterly bereft mother by a cruel 20 years. Suddenly, her regime of funereal black rooms, veils, and never leaving the house makes tragic sense.

After a lifetime of being camera ready, Oldoini passed on November 28, 1899. She would not live to see the Exposition where she planned to debut her photos. By dying in 1899, she also missed out on the 20th century—an era where photography would only continue to dominate media and society.

Aside from taking up with Napoleon III in full view of her husband Francesco, the countess also literally bankrupted the man with her expensive tastes.

Aside from taking up with Napoleon III in full view of her husband Francesco, the countess also literally bankrupted the man with her expensive tastes.

Sure, the countess was beautiful, but beauty is only skin deep. Her memoirs reveal some disturbing and embarrassing details. In her own writings, she refers to herself in the third person. One choice line? “The Eternal Father did not know what he was creating the day he sent her into the world.”

Sure, the countess was beautiful, but beauty is only skin deep. Her memoirs reveal some disturbing and embarrassing details. In her own writings, she refers to herself in the third person. One choice line? “The Eternal Father did not know what he was creating the day he sent her into the world.”